Student outcomes that are impacted by, and factors that impact across, the transition process

A brief summary of the academic and social-emotional outcomes impacted by the transition process follows.

A number of studies highlight the impact of school transition on academic outcomes as well as other factors, however, findings are mixed and tend to be quite specific to the studies in question.

For example:

- Goldstein, Boxer and Rudolph (2015) found that higher amounts of transition stress predicted lower grades, lower connectedness to school, and increased school-related anxiety.

- Other researchers have investigated the impact of transition on academic progress by contrasting students’ academic performance during upper primary school with their performance in early secondary school. For example, Carmichael’s (2015) research showed that, on average, students who remained at primary school for Year 7 had slightly higher growth in mathematics performance from Year 5 to Year 7, than that of students who had moved to secondary school for Year 7.

- Pauses to academic progress or achievement during the transition period have been linked to students’ adjusting to the new curriculum and pedagogy of the secondary school system (Attard, 2010).

Other studies, however, contradict the academic-decline-due-to-transition narrative:

- Langenkamp (2011), notes the lack of evidence for transition in isolation influencing students’ academic outcomes. This research suggests instead that where a decrease in academic achievement is shown, it tends to be associated with other social difficulties or a mid-year school move.

Other studies highlight the influence of self-concept and motivation on academic progress:

- Academic self-concept – the way in which a student thinks about themselves academically (Bong & Skaalvik, 2003) – is an important idea. This is because the frame of reference through which students reflect and create their self-concept changes as they enter the secondary school system. In secondary school, students are faced with new academic standards and ways of learning, different expectations from teachers and a new set of peers for social and academic comparison (Becker & Neumann, 2018; Gniewosz, Eccles & Noack, 2011), and this affects their self-concept.

- In the USA context, some researchers note that the transition from elementary to middle school is associated with a decrease in academic motivation (Goldstein, Boxer & Rudolph, 2015; Towns, 2011). Goldstein and colleagues’ (2015) explain that students who are more stressed across the transition to middle school are at greater risk of experiencing lower academic motivation and performance. Towns (2018) suggests that developing a sense of belonging to school may help, as school-belonging is shown to increase academic motivation, along with other positive social, emotional and academic markers.

In addition to academic outcomes, studies have also shown the influence of school transition on social and emotional wellbeing. For example, in the Australian context, a sense of belonging to a school has been correlated with positive health and academic outcomes and positive social and emotional wellbeing.

- Waters, Cross and Shaw (2010) show that the school transition period is a predictor of present and future school connectedness. Importantly, however, their research shows that a positive student transition experience is also correlated with positive wellbeing indicators such as:

- higher family connectedness,

- higher connectedness with school and teachers in the transition and following year,

- more extracurricular participation,

- more pro-social skills, and,

- fewer behavioural, emotional, peer and classroom problems.

- Vaz and colleagues’ (2015) findings show that belongingness is generally stable over the primary–secondary transition period and is associated with students’ backgrounds and personal attributes such as coping skills and social acceptance.

- Conversely, Waters, Lester, Wenden and Cross (2012) found that up to a third of students reported a “‘difficult’ or ‘somewhat difficult’ transition to their new school”. These students were at greater risk of poorer social and emotional health up to a year later (p.196).

The findings from research into levels of physical activity after the transition to a secondary school environment are also concerning:

- Rutten, Boen and Seghers (2014) found that even though pedometer-measured exercise rates did not particularly change, sedentary behaviours – such as more time on homework and recreational computer use – increased across the two-year school transition period.

- Marks, Barnett, Strugnell and Allender (2015) showed a decrease in student physical activity and increases in sedentary behaviour during the primary–secondary school transition.

- Ridley and Dollman’s (2019) study of female students showed that physical activity particularly declined across the school transition period, most noticeably during recess and lunch break times.

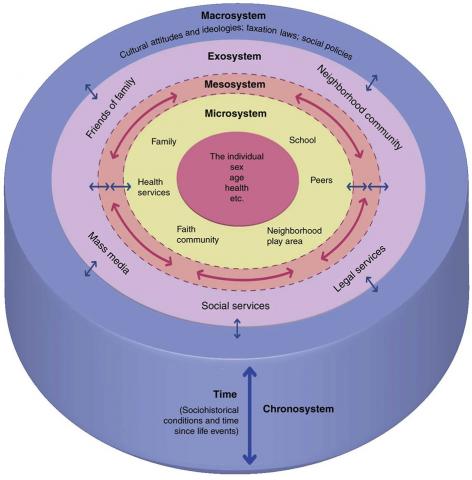

Indicators from a student’s environment (Bronfenbrenner – right) have been correlated with positive and negative wellbeing. Specifically, positive wellbeing indicators from a student’s environment are correlated with a positive transition (Waters, Cross & Shaw, 2010), and negative wellbeing indicators are correlated with a poor transition (Waters, Lester, Wenden & Cross, 2012). It is therefore important to consider environmental factors for each student. Particular factors include students’ social support structures (e.g., family, friends, community) (Pendergast et al., 2018), and their socio-economic and socio-educational backgrounds (Vaz et al., 2014). However, additional learning challenges (e.g., ADHD, dyslexia), and students’ social-emotional capabilities (e.g., persistence, ability to make new friends) (Maguire & Yu, 2014) are also impacted by elements in a student’s environment.

In addition to the individual factors, there are also systemic factors that impact transition, namely the need to move schools at all, and the differing natures of primary and secondary education. Vaz (2010) notes that changing school campuses during adolescence and moving from a child-centred primary school to an achievement-centred secondary school are potentially stressful events that can prompt transition difficulties (p.108). Other researchers consider the differences in impact on students transitioning at different ages (for example, Holas & Huston, 2012, who researched students transitioning at fifth versus sixth grade in the USA), at different times to their peers (for example, Langenkamp, 2011) or propose that fewer transitions – using K–8 instead of K–5 then 6–8 – could help in mitigating negative outcomes (for example, Hensley, 2009).